The last silk dress in the Confederacy

10,000 men descending from the clouds might not in many places do an infinite deal of mischief

His neighbors weren’t thrilled by the suggestion, refusing the teenager access to their dog. A cat “borrowed” from a storefront would have to suffice. Thaddeus S.C. Lowe was hoping for a repeat performance from the feline, something bigger and better than the initial experiment – but first it would have to survive. The animal was, understandably, terrified by the whole endeavor, balled up inside a cage and battered by winds a considerable height. The mysterious flying object reportedly made headlines the following day, courtesy of concerned citizens.

The cat mercifully survived the whole ordeal only slight worse for wear, darting away the moment the cage was opened on the ground. The entire spectacle was enough to convince Lowe to never again experiment on an animal in such a way. Subsequent trials found him tethering lanterns, flags and other inanimate objects, all while holding out hope that he might someday construct a kite large enough to lift himself into the air.

The dream never changed, though his chosen instrument ultimately would a few years later. An 18-year-old Lowe and his brother could hardly contain their excitement when a traveling chemistry lecturer arrived in Boston. Appearing under the self-assigned honorific “Professor,” Reginald Dinkelhoff was, by all accounts, a compelling speaker. A large proponent of the visual aid, he filled soap bubbles full of hydrogen, which remained aloft to the amusement of the audience.

Lowe’s hand was the first to shoot up when Dinkelhoff asked for a volunteer. The young man rushed to front of the lecture hall, eager to partake in whatever the Professor might have in mind. Lowe’s enthusiasm quickly earned him a spot as permanent assistant – and soon he set out on a solo lecture tour. This work would, however, only serve as an on-ramp into the broader world of aeronautics -- his true calling from day one.

His brief foray into chemistry was soon eclipsed by the study of lighter than air craft. Nearly half-a-century before his birth, Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier and François Laurent d'Arlandes had performed the first manned flight in Paris, following several experiments with chickens, ducks and sheep. Kite enthusiast Benjamin Franklin was made aware of the event during a diplomatic trip to France the same year.

He soon pondered how such craft might someday become instruments of war. “Five thousand balloons, capable of raising two men each, could not cost more than five ships of the line,” he soon noted in a letter, “and where is the prince who can afford so to cover his country with troops for its defense as that 10,000 men descending from the clouds might not in many places do an infinite deal of mischief before a force could be brought together to repel them?”

Franklin also suggested that such craft might soon be deployed to spy on enemy armies. By the end of the century, the French had already begun to use balloons during military campaigns, only to have Napoleon fully disband the French Balloon Corps in 1799. Lowe was keenly aware of the technology’s use in warfare and was wholly opposed to the phenomenon.

He did, however, see plenty of practical use for the massive balloons he began to build and fly. After four years of work, the first transatlantic cable was completed in 1858 and inaugurated with a congratulatory letter from Queen Victoria to James Buchanan. Within three weeks, the cable was rendered entirely useless. Lowe volunteered City of New York, his recently finish 103-foot balloon. He reasoned that such a craft would be able to carry information between the continents at a far higher speed than ship travel.

A first attempt was cut short when the wind tore a hole in the balloon’s side. The outset of the American Civil War soon ended the project altogether. Three months after the war began, Lowe found himself in his Enterprise balloon 500 feet above the White House. A wire emerged from the balloon’s basket, running to the ground, where it culminated in a Morse telegraph. He dictated the message to the operator standing beside him in the basket,

Dear Sir:

From this point of observation we command an extent of our country nearly fifty miles in diameter. I have the pleasure of sending you this first telegram ever dispatched from an aerial station, and acknowledging indebtedness to your encouragement for the opportunity of demonstrating the availability of the science of aeronautics in the service of the country.

I am, Your Excellency's obedient servant,

T.S.C. Lowe

A decade after Lowe had criticized balloon use on the battlefield, the President installed him as the first head of the Balloon Corps. His balloon was deployed at the first major battle of the war, just north of Manassas, Virginia. The engagement, however, did not play out as expected. Union soldiers unaware of the experiment began firing at Lowe, a civilian, who was not dressed in uniform. He took evasive action and landed behind enemy lines, waiting overnight to be rescued by the army who had shot at him.

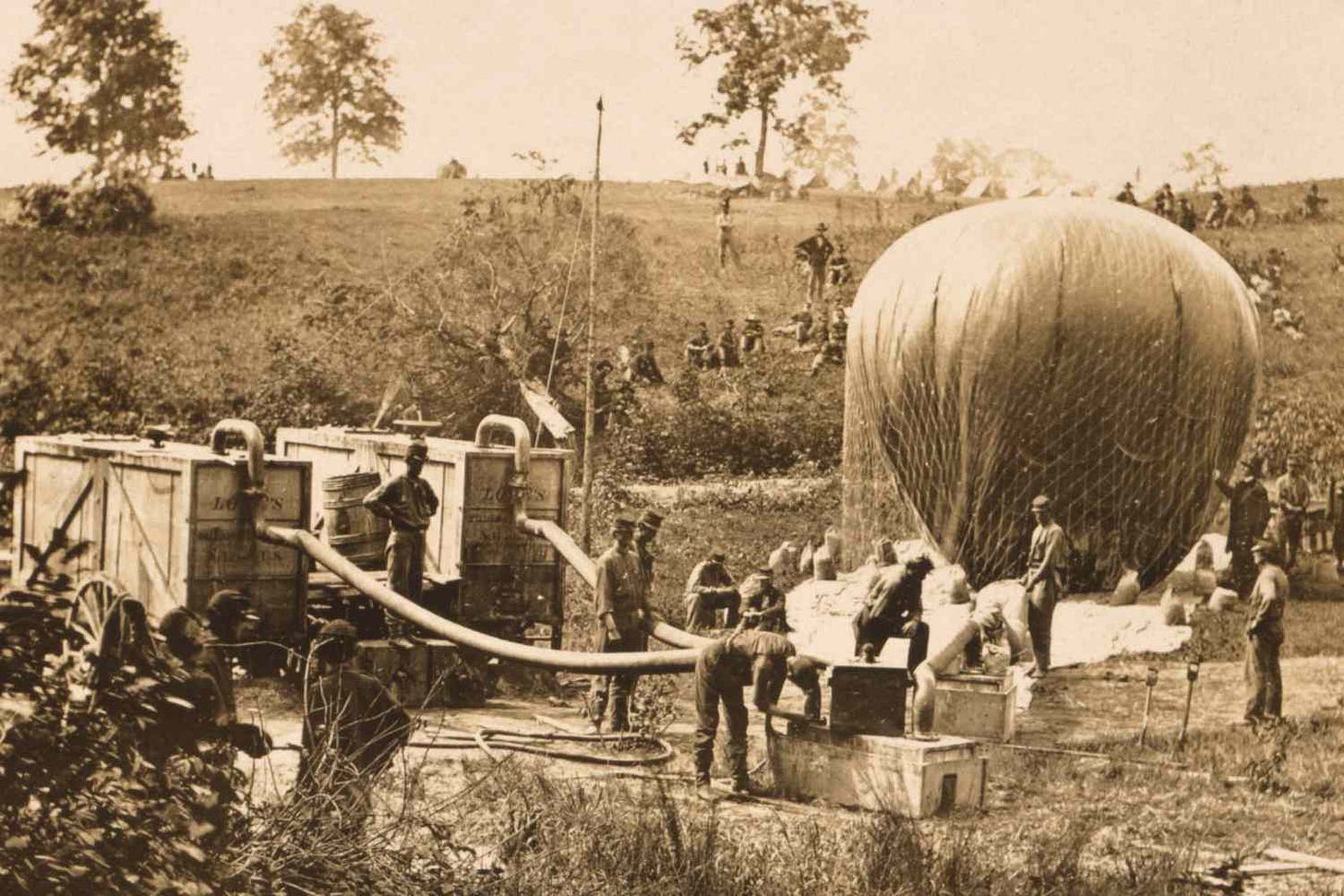

A subsequent campaign was considerably more successful, as the army loaded hydrogen gas generators and two balloons onto the back of General Washington Parke Custis, a former coal barge. Lowe and company spied on confederate forces from relative safety above the Potomac.

“I have the pleasure of reporting the complete success of the first balloon expedition by water ever attempted,” Lowe wrote of the early aircraft carrier. “I left the Navy yard early Sunday morning , the 10th instant, with a lighter towed out by the steamer Coeur de Lion, having on board competent assistant aeronauts, together with my new gas generating apparatus, which, though used for the first time, worked admirably.”

Confederate attempts to counter Union balloon efforts failed miserably on multiple occasions. A general of the Southern forces outlined one such incident in a letter to Lowe,

While we were longing for balloons that poverty denied us, a genius arose and suggested that we send out and get every silk dress in the Confederacy to make a balloon. It was done and soon we had a great patchwork ship […] One day it was on a steamer down the James River when the tide went out and left it high and dry on a bar. The Federals gathered it in, and with it the last silk dress in the Confederacy. This was the meanest trick of the war.

Not long after, Lowe contracted malaria while on duty along the banks of the Chickahominy River. When he returned to work after a month on the mend, the Balloon Corps was on its last legs. By August 1863, the branch was no longer utilized by the Union Army.

Sources:

Above the Civil War by Eugene Block

Benjamin Franklin on Balloons: A Letter Written from Passy, France, January Sixteenth MDCCLXXXIV