The energy of this ether is boundless and can hardly be comprehended

What name to give his new form of force he does not know, but the basis of it all, he says, is vibratory sympathy

The discovery of interatomic ether was poised to transform the world, just as American was entering its second industrial revolution. Like the legend of Newton’s Apple some 200 years prior, the discovery of this revolutionary element was nothing short of pure serendipity.

A tuning fork had provided inspiration. Speaking to The New York Times in 1888, John E.W. Keely broke things down simply.

“Stripping the process of all technical terms, it is simply this: I take water and air, two mediums of different specific gravity and produces from them by generation an effect under vibrations that liberates from the air and water an inter atomic ether,” he told the paper. “The energy of this ether is boundless and can hardly be comprehended. The specific gravity of the ether is about four times lighter than that of hydrogen gas, the lightest gas so far discovered.”

It was a remarkable discovery – likely the 19th century’s greatest – and it had come from the simplest of places, nearly as unassuming as the man who made it. Keely’s roots were humble. Born outside of Philadelphia, he was orphaned at an early age during an epidemic and raised by his grandparents. A factotum of jobs followed: carpenter, orchestra leader and circus performer, among others.

He had no science background to speak of, but time spent as a mechanic provided some foundation on which to build out his radical theories — and roughly 2,000 machines. By 1874, a year after stumbling upon the theory, he demonstrated an early prototype to a small crowd gathered in Philadelphia.

"People have no idea of the power in water,” Keely told the press. “I propose to run a train of thirty cars from Philadelphia to New York at the rate of a mile a minute, out of as much water as you can hold in the palm of your hand."

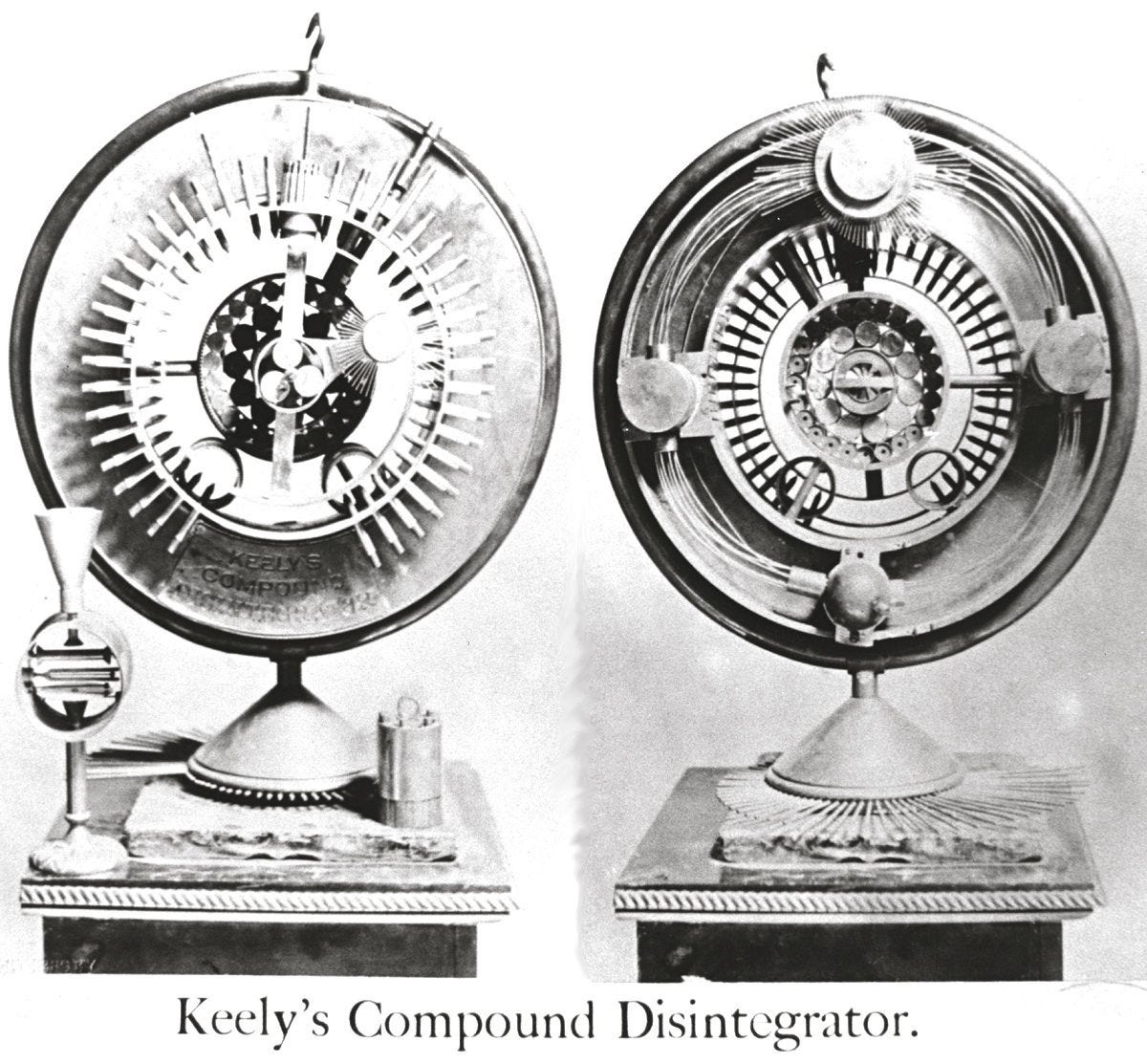

The etheric generator certainly looked the part. And pouring tap water into the machine gave a reading of 10,000 PSI, transforming the water into vapor and powering up nearby machines. Several in attendance purchase Keely Motor Company on the spot. The technical terms Keely used for the technology were are fluid as the water that powered it – to be expected, perhaps, from a consummate outsider.

A decade later, Keely gave the world the vaporic gun – “a breechloading rifle weighing 500 pounds,” according to the inventor. Six drops of water were sufficient enough to fire 20 bullets, weighing five ounces a piece. He told the media that even he was astounding by what the device was capable of, with the velocity of the bullets only increasing as they continued to fire.

The media declared a demonstration of the machine “a great success.”

“My experimenting days are over,” Keely told a reporter days later “This will develop my active enterprise. Complete success is very near at hand.” He went on to compare interatomic ether favorably to both gunpowder and nitroglycerine. Keely Motor Company stock rose once again.

By 1887, Keely had abandoned interatomic ether, owing to the impracticality of harnessing the phenomenon. Much to his shareholders’ excitement, however, he had stumbled upon something even more compelling.

“What name to give his new form of force he does not know, but the basis of it all, he says, is vibratory sympathy,” The Times wrote, reporting the minutes for a financial meeting at which Keely was not present. “He had no doubt that he would sooner or later be able to produce engines of varying capacity, so small as to run a sewing machine and so large and powerful as to plow the sea as the motive force in great ships. His ultimate success, he still holds, will be greater than even his most sanguine advocates have predicted.”

Keely and his technologies inspired their share of detractors over the decades. His lack of transparency and ever-extending deadlines didn’t do much to help the inventor’s case – nor did the fact that he regularly turned down any opportunity to speak with his peers in the sciences.

Scientific American, in particular proved a constant thorn in the inventor’s side. “Nothing more lamentably exhibits the general lack, in this country, of elementary scientific education, than the editorial comments upon this subject by many of the papers,” the publication wrote in 1875.

The piece, titled “The Keely Deception,” ended on a prophetic note. “The price of the Keely stock, which at one time was very high,” it notes, “is beginning to ebb, and in a short time all the beautifully engraved stock certificates will doubtless find their way into the cellars of the rag and paper dealers.”

When the inventor died of pneumonia at the end of the following decade, Scientific America visited Keely’s labs to test their longstanding theories.

“Many of our older readers will remember that from the very first this journal was emphatic in its opposition to the Keely mania, and endeavored, we think, with considerable success, to check, if it could not wholly prevent, such obvious swindling of the public,” it wrote. “We pointed out that all of the results obtained by Keely could be duplicated by using compressed air in suitable apparatus, and in 1884, in the case of the Keely gun, conducted experiments which proved that in this case, at least, we were correct.”

Shortly after the report was published, the Keely Motor Company was dissolved, a definitive ending for his perpetual motion machines.

Sources:

Keely, John (Ernst) Worrell (1837-1898) https://www.encyclopedia.com/science/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/keely-john-ernst-worrell-1837-1898

The Etheric Force Machine https://www.neh.gov/humanities/2010/mayjune/curio/the-etheric-force-machine

Local Brevities https://www.newspapers.com/clip/78560829/local-brevities-29-sep-1884-the/