A very strange, enchanted boy

I started a search for the strange fellow, who left his song with me

He sits cross-legged in the middle of the stage, in front of a bicycle turned on its side. His appearance is shocking, perhaps, a stark contrast to Dwight Weist, who crouches by his side, a large, white carnation bursting from the pocket of his tuxedo jacket. The consummate mustachioed radio man appears genuinely interested, as he addresses the subject with rehearsed questions.

“Did you know King Cole?” he asks, holding out the microphone.

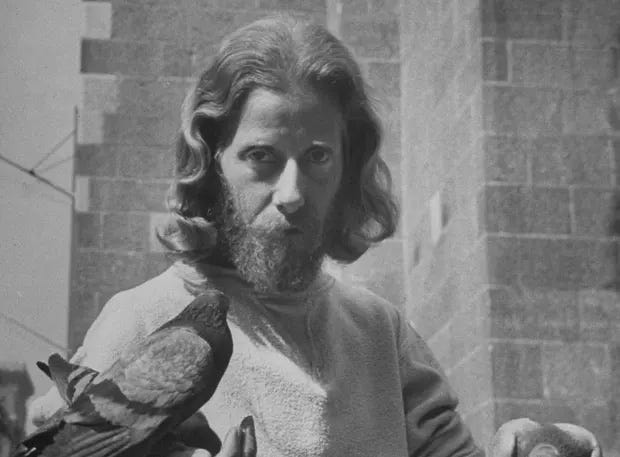

“No,” the man answers, eyes locked to the script in his lap. “I had never met the man who has played such an important part in my life.” His words are awkward. The pair had rehearsed the conversation, but eden ahbez (all lowercase, as only God deserves to be capitalized) sounds as if he’s reading his answers aloud for the first time. He’s stilted, but not visibly nervous. Dressed in the drab, pale clothing of a man not particularly concerned outward appearances, shoulder length hair and a full beard complete the picture.

The year is an important one for TV. A week later, Milton Berle will debut the first episode of Texaco Star Theater, the show that will earn him the nickname, "Mr. Television.” In a dozen more days, another variety show, Talk of the Town will premier with guests Dean Martin and Jerry, emceed by first-time TV host, Ed Sullivan. Its network, CBS, had only begun television operations two months prior.

It's not surprising, then, that We People is closer to a filmed radio program than anything resembling a modern TV talk show. The first episode of the CBS series still has plenty of kinks to work out. Time’s review of the inaugural airing is especially critical, noting,

Televiewers last week got a look at a radio program in action, We the People. It looked worse than it sounded. A guest named Evil-Eye Finkle made evil eyes at the camera; Mrs. Spencer Tracy fastened her eyes to the script; Fred Allen mostly looked glum; Nat “King” Cole sang Nature Boy and Composer Eden Ahbez [sic] showed his curls. Master of Ceremonies Dwight Weist went his own way, all but ignoring the prying eye of the telecamera.

Things pick up when Weist and ahbez stand and walk to their left. Cole, having just flown in from Chicago, is waiting for the two men behind a podium, script in hand. “Nature Boy,” the host says, helpfully, “meet Nat Cole.”

The guests recount how their paths crossed the previous year. A non-meeting of sorts. “ ‘Nature Boy’ almost wasn’t published,” the singer explains. “The doorman at the theater wouldn’t let ahbez backstage.”

Given the man’s appearance, it’s perhaps not surprising that he wasn’t able to make it inside Los Angeles’ Lincoln Theater. Cole’s valet, however, agreed to pass along an envelope, and the singer was instantly taken by the song on the tattered sheet music. But its author hadn’t left his address.

“I started a search for the strange fellow, who left his song with me,” Cole explains, “and I had to leave on a road tour, before I found him.”

ahbez had settled in Los Angeles six years prior. Now in his mid-30s, he’d spent years in the Brooklyn Hebrew Orphan Asylum, before being adopted by a midwestern family at age nine. He performed as pianist in Kansas City during the depression and moved to Miami, where he discovered vegetarianism and yoga. He claimed to have walked across the country eight times, before finally settling in Southern California with a bicycle, sleeping bag and a juicer. He found work at Eutropheon, a health food store and raw food restaurant that had operated in Laurel Canyon since 1918.

A friend of Cole’s tracked the man down weeks later, while the singer was still on tour. ahbez had taken up residence in the hills, beneath one of the Hollywood sign’s Ls.

Cole’s version of the song, “Nature Boy,” sold a million copies in its first year. It hit number one on Billboard, remaining on the charts for 15 weeks, helping to skyrocket the singer to national fame. It’s among the most haunting and beautiful songs ever to reach the top of the pop charts, recounting the story of “a very strange, enchanted boy.” Shy, but wise, he had already spent a good many years traveling the world.

“And while we spoke of many things,” the story continues, “Fools and kings, this he said to me: ‘The greatest thing you'll ever learn is just to love and be loved in return.’ ”

One would be forgiven for assuming, as Weist does, that ahbez is titular “nature boy.” While the song’s author is now regarded as having been a hippie long before the word entered the popular vernacular, Bill Pester had ahbez beat by a couple decades. A longtime traveler, he settled in California in 1916, earning the name "the Hermit of Palm Springs,” for a lifestyle that involved homemade sandals and a palm hut shelter he’d built by hand.

The same year Cole released his single, Hollywood paid ahbez $10,000 to use “Nature Boy” as the score to an anti-war film, starring a 12-year-old Dean Stockwell as the titular Boy with Green Hair. Life would later report that the song had netted him $20,000, by May 1948.

Standing to the side of both Cole and ahbez, Weist asks the latter whether he’s even seen that much money in his life. “All the money in the world will not change my way of life,” he answers. “‘Cause all the money in the world cannot give me the things I have.”

He offered the same sentiment to Life, explaining, “It’s not so much what you want, it’s keeping away from the things you don’t want.” The magazine notes his struggles with the newfound fame, explaining that ahbez is considering upgrading the bicycle to a jeep, “to flee back to nature."

Sources:

Life May 10, 1948, "Nature Boy"

Mother nature’s son https://www.theguardian.com/music/2022/jan/25/mother-natures-son-the-exotic-world-of-songwriter-eden-ahbez

Radio: Busy Air https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,854928,00.html

Eden Ahbez 1948 gulf oil Cole & Boone https://youtu.be/U7ddLymh8vE